Each shot and each scene is like music. If there was only one note played for any time, it would become monotonous. Different, contrasting notes make music interesting. When planning shots and cutting scenes, it's important to consider how they will play out against each other, to create the mood required for the story. A less intense scene will need less contrast, and vice versa. If two similar scenes are put next to each other, the movie may drag.

Here's an example of different scenes next to each other in Mission Impossible Ghost Protocol. When planning the mission, the scene is in a confined interior space, with blue light. The scene after is bright with miles of clear view and a neutral color palette. Right after, however, we're in the middle of a dust storm that feels confining and has red colors throughout. The contrast makes the movie interesting and feels bigger.

Within a scene, each shot should be planned in regards to the contrast required for the story. Shot Contrast can be controlled based on how large subjects are in frame, angles, and color. I've put a Black color under intense shots, Grey for less intense and White for the least intense shots. As you can see, the beginning has sporadic intense shots, then at the end the intensity is ramped up. This subconsciously gives the viewer an orchestrated experience that they'll enjoy.

CG Camera

My thoughts on Camera, Lighting, Directing and Editing which can hopefully spark interest and help others in the wonderful new world of Computer Generated Films and Games.

Monday, 1 July 2013

Sunday, 26 May 2013

Giving Shots Purpose

Time and time again, I've seen shots in films and games that have no

real purpose or focus. You should be able to justify each shot as to

what it's for, and what it's trying to do to tell a story.

I'll start with the example of a simple establishing shot. Often, I see a shot like this;

Although it establishes the location, if we cut to a shot of the character right after, the viewer would have no idea where in this city we are supposed to be. Plus, there is no singular focus to the shot. What's the point? Where does our eye go?

In the next example, our focus is in the center of frame, and we push through the city to reveal a bright blue swimming pool and then our hero swimming in it. Now we know where exactly we are, and what the focus is.

Always think of shots in terms of what would you, the film maker, want to show the viewer to tell the story. Always think in terms of clear focus. Could you tell the story in a series of stills without needing dialogue? If you can't, try to simplify your shots into beats that have distinct purpose. Here's a scene from "The Road", that is powerful and requires no dialogue.

In the first few shots, we see that the setting is a dead forest surrounding a road. Two characters emerge from a large, pointy overturned stump. The color is bleak and dark, and the characters are wearing coats. The feeling is cold, death and despair.

Following the set-up, we see that the road the characters are traveling on is in very bad shape after a landslide. They have a shopping cart full of supplies, are having a hard time traversing the decaying road, but are warm with each other. Obviously they are on the road to leave this desolate land, are friends or family and have everything they own with them.

Showing the characters off to the side, and small in frame, signifies their weakness. The surroundings show there is no life. Thousands of dead trees in the water show that something awful and abnormal has happened.

The characters pull out a ripped map to show the road that has been established and where they are. A tree falling in the background confirms that the world is dying around them.

The characters scavenge through a town trying to find supplies, but the only thing they find is a little piece of bone with some rotten meat on it. It looks like a great find to them, and the older man gives it to the boy to eat. Obviously he cares more for the boy than himself, and that survival is almost impossible in this dead world.

So, there's just one example of a powerful scene that required nothing but simple and powerful images strung together in a sequence. If you add sound and motion, it could be even more powerful, but the foundation is there. If you build your foundation on dialogue, the scene will be flat.

I'll start with the example of a simple establishing shot. Often, I see a shot like this;

Although it establishes the location, if we cut to a shot of the character right after, the viewer would have no idea where in this city we are supposed to be. Plus, there is no singular focus to the shot. What's the point? Where does our eye go?

In the next example, our focus is in the center of frame, and we push through the city to reveal a bright blue swimming pool and then our hero swimming in it. Now we know where exactly we are, and what the focus is.

Always think of shots in terms of what would you, the film maker, want to show the viewer to tell the story. Always think in terms of clear focus. Could you tell the story in a series of stills without needing dialogue? If you can't, try to simplify your shots into beats that have distinct purpose. Here's a scene from "The Road", that is powerful and requires no dialogue.

In the first few shots, we see that the setting is a dead forest surrounding a road. Two characters emerge from a large, pointy overturned stump. The color is bleak and dark, and the characters are wearing coats. The feeling is cold, death and despair.

Following the set-up, we see that the road the characters are traveling on is in very bad shape after a landslide. They have a shopping cart full of supplies, are having a hard time traversing the decaying road, but are warm with each other. Obviously they are on the road to leave this desolate land, are friends or family and have everything they own with them.

Showing the characters off to the side, and small in frame, signifies their weakness. The surroundings show there is no life. Thousands of dead trees in the water show that something awful and abnormal has happened.

The characters pull out a ripped map to show the road that has been established and where they are. A tree falling in the background confirms that the world is dying around them.

Finally we see a hint of civilization, but the gas station is abandoned, and all gas is gone. More than a simple forest fire, something is seriously wrong with the world.

The characters scavenge through a town trying to find supplies, but the only thing they find is a little piece of bone with some rotten meat on it. It looks like a great find to them, and the older man gives it to the boy to eat. Obviously he cares more for the boy than himself, and that survival is almost impossible in this dead world.

So, there's just one example of a powerful scene that required nothing but simple and powerful images strung together in a sequence. If you add sound and motion, it could be even more powerful, but the foundation is there. If you build your foundation on dialogue, the scene will be flat.

Sunday, 14 April 2013

Showing Power

A couple ways to show power is to have powerful people and organizations centered in frame, higher than others and bigger than anything else.

In this frame, from Children of Men, the government building dwarfs the car carrying Clive Owen. It's directly centered in frame, which makes it appear solid and powerful. Lines from the road lead directly to the building, guiding our eye to the building and emphasizing its importance.

When a busload of citizens enter a government facility, it's clear to see who's in charge. The officer stands tall over everyone, directly in the center of frame. All perspective line lead to him.

With the statue, the massive room, the large dogs, centered frame and perspective lines, there's no doubt that the guy at the end of the hall is powerful (and egotistical).

In contrast, as Clive Owen's character is weakened to the point of death and things seem hopeless, he is placed to the far left and bottom of frame. By doing this, his power is reduced to nothing. The Negative Space overwhelms him and when the boat emerges from the fog it's more centered, as it's taken control.

The art direction for this space creates a massive clean room with straight bars on all the windows and simple colors. The sense from this, is it's large and powerful, but bleak and controlling. Bars are, of course, symbolic of jails, institution and security.

Opposite of that, this smaller space has many colours, straight lines are broken using books, plants, lights, etc. This helps give a comforting, lived-in look and feel.

Using Art Direction and Cinematography means the story never needs to specifically say which place is powerful, the viewer can feel it. Imagine if the government office was in the cozy room example! It would completely change the feeling of the story.

However, since we expect evil government offices to be in large cold buildings, putting them in direct contrast could be more powerful, if set up well!

In this frame, from Children of Men, the government building dwarfs the car carrying Clive Owen. It's directly centered in frame, which makes it appear solid and powerful. Lines from the road lead directly to the building, guiding our eye to the building and emphasizing its importance.

When a busload of citizens enter a government facility, it's clear to see who's in charge. The officer stands tall over everyone, directly in the center of frame. All perspective line lead to him.

With the statue, the massive room, the large dogs, centered frame and perspective lines, there's no doubt that the guy at the end of the hall is powerful (and egotistical).

In contrast, as Clive Owen's character is weakened to the point of death and things seem hopeless, he is placed to the far left and bottom of frame. By doing this, his power is reduced to nothing. The Negative Space overwhelms him and when the boat emerges from the fog it's more centered, as it's taken control.

The art direction for this space creates a massive clean room with straight bars on all the windows and simple colors. The sense from this, is it's large and powerful, but bleak and controlling. Bars are, of course, symbolic of jails, institution and security.

Opposite of that, this smaller space has many colours, straight lines are broken using books, plants, lights, etc. This helps give a comforting, lived-in look and feel.

Using Art Direction and Cinematography means the story never needs to specifically say which place is powerful, the viewer can feel it. Imagine if the government office was in the cozy room example! It would completely change the feeling of the story.

However, since we expect evil government offices to be in large cold buildings, putting them in direct contrast could be more powerful, if set up well!

Monday, 1 April 2013

Guiding the Eye with Match Cuts

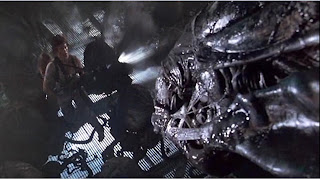

Especially when shooting fast paced scenes, guiding the eye into the right area of the screen is quite important. If a shot is 15 frames long, and it's going to be shown on a 70 foot screen, the audience has to know where to look. They can't take the time to search for what's important. With planning it's possible to guide the viewers eye to control what they see and know what's important. Many people just shoot for the center to easily match up, but that can be less interesting to see. Here's a quick example from Aliens, to show what a Match Cut can look like;

In the next shot, our eye is guided to the screen with the help of the angles of the Actor's faces and the fact that the screen is the brightest part of the shot. It's on the left of frame, and when we cut to the next shot, the important part of this set (where they'll land) is the bright area to the left of frame.

When we cut back inside the ship, Ripley is speaking on frame left and the Carter speaks at the end of the shot, so our eye is drawn towards screen right. We cut to the next shot that has the ship on frame right.

Throughout this sequence, the viewer knew where to look the entire time. Very well planned shooting, that doesn't distract the audience. However, if you want to increase the feeling of tension, or the character being lost, it may feel better to have the viewer search a bit in the frame.

Although the proceeding cut is just TV signal distortion, our eye looks at it immediately and in the next shot, we're drawn to the Marine's gun. Next, I'll show a sequence of shots as the ship lands on the planet's surface.

In these two shots our eye is drawn towards the top of the screen with the help of the HUD cross. Then we cut to the ship at the top of screen.

In the next shot, our eye is guided to the screen with the help of the angles of the Actor's faces and the fact that the screen is the brightest part of the shot. It's on the left of frame, and when we cut to the next shot, the important part of this set (where they'll land) is the bright area to the left of frame.

When we cut back inside the ship, Ripley is speaking on frame left and the Carter speaks at the end of the shot, so our eye is drawn towards screen right. We cut to the next shot that has the ship on frame right.

Throughout this sequence, the viewer knew where to look the entire time. Very well planned shooting, that doesn't distract the audience. However, if you want to increase the feeling of tension, or the character being lost, it may feel better to have the viewer search a bit in the frame.

Monday, 25 March 2013

Camera Height for Dramatic Effect

Camera height can give a subtle yet dramatic feeling to the viewer. Since our perspective is from that of the camera, we automatically associate ourselves with it. A higher camera than the subject means we are looking down on that person, and we will feel more powerful as a result. A lower camera puts the viewer in a vulnerable position and looking up will usually show the subject as being more powerful. However, if the context is suspenseful, we will also see less far and our perspective will be unnervingly skewed.

In these examples, from the Alien franchise, a high camera will give a sense that we (the Alien) are bigger and watching them, and that the subject is powerless and/or unaware of our presence. It's quite unnerving for the subject (who we hopefully care about). A higher camera will also have the effect of limiting the view around the subject, which in itself is suspenseful.

Conversely, here's some examples where the camera is low. Usually this gives the impression the subject is in control, but in Alien it is meant to feel unnerving, to hide the view around the subject and to make the viewer feel more vulnerable.

In these examples, from the Alien franchise, a high camera will give a sense that we (the Alien) are bigger and watching them, and that the subject is powerless and/or unaware of our presence. It's quite unnerving for the subject (who we hopefully care about). A higher camera will also have the effect of limiting the view around the subject, which in itself is suspenseful.

Conversely, here's some examples where the camera is low. Usually this gives the impression the subject is in control, but in Alien it is meant to feel unnerving, to hide the view around the subject and to make the viewer feel more vulnerable.

Monday, 11 March 2013

Creating a simple Camera Rig

One of the first things that should be done when starting a production is to create a good camera rig. A good camera rig will make it easier to animate and compose shots, as well as save time, make the camera feel more realistic and can increase creativity.

The basis of this simple camera rig is using the Aim Constraint to control the camera rotation. For me, the Aim is the best way to control the camera, because counter rotating is not necessary and it works as composing does in reality. Think about this; if our subject is our hero , and we crane from a rooftop to be right in front of the hero, our aim will still be the same... the hero. In many productions, you need to constantly key and rotate the camera, but I feel that's not intuitive.

The first thing I like to do is scale the default camera to the dimensions of a real camera. This is better for real-world Previs, but also makes you closely adhere to reality. I find that scaling to 26 matches a 35mm film camera.

I like to set the Film Back to "35mm Full Aperture" and then controlling the film size through the Render Settings.

Now, create a locator and put it where the Tripod would connect to the camera and then put the Pivot Point of the camera away where the locator is. This small change can make the camera look more realistic during Tilts and Pans, since this is where real cameras rotate from.

Now, create a Locator a few feet from the camera and constrain the aim of the camera to it, while maintaining the offset.

Now, to control that Locator, I set up 2 NURBS circles, a GLOBAL and LOCAL with the locator grouped under them as "Aim_Ctrl". Now we have two controllers controlling the aim. I usually constrain the Global to the subject or leave it stationary and then animate the Local to recompose and give a "human" feel to. We can think of this as the Subject being the Global aim and any re-composition or movement being added to that.

Then create 3 more NURBS circles, a UNIVERSAL, GLOBAL and LOCAL that will control the camera body. Put the Aim_Ctrl group under the UNIVERAL NURBS circle. Freeze the transforms on all NURBS controllers and Delete the History. Hide the Locators so they don't get in the way.

On one of the Controllers, create a new Attribute called "Aim_Ctrl" and key the aim constrain at 0 and 1. This will allow you to easily turn off the aim as needed. Sometimes, in environmental or locked off shots, it's easier to keep the camera without an aim.

Now that this simple rig is finished, you can see that the UNIVERSAL control will move both the aim position and the camera. Moving the GLOBAL or LOCAL will move the camera separately from the aim. You can constrain the GLOBAL aim controller to the subject, and move the LOCAL to recompose as needed.

This is just a start, the more controls you can add to make shooting fun and quick, the better!

The basis of this simple camera rig is using the Aim Constraint to control the camera rotation. For me, the Aim is the best way to control the camera, because counter rotating is not necessary and it works as composing does in reality. Think about this; if our subject is our hero , and we crane from a rooftop to be right in front of the hero, our aim will still be the same... the hero. In many productions, you need to constantly key and rotate the camera, but I feel that's not intuitive.

The first thing I like to do is scale the default camera to the dimensions of a real camera. This is better for real-world Previs, but also makes you closely adhere to reality. I find that scaling to 26 matches a 35mm film camera.

Now, create a locator and put it where the Tripod would connect to the camera and then put the Pivot Point of the camera away where the locator is. This small change can make the camera look more realistic during Tilts and Pans, since this is where real cameras rotate from.

Now, create a Locator a few feet from the camera and constrain the aim of the camera to it, while maintaining the offset.

Now, to control that Locator, I set up 2 NURBS circles, a GLOBAL and LOCAL with the locator grouped under them as "Aim_Ctrl". Now we have two controllers controlling the aim. I usually constrain the Global to the subject or leave it stationary and then animate the Local to recompose and give a "human" feel to. We can think of this as the Subject being the Global aim and any re-composition or movement being added to that.

Then create 3 more NURBS circles, a UNIVERSAL, GLOBAL and LOCAL that will control the camera body. Put the Aim_Ctrl group under the UNIVERAL NURBS circle. Freeze the transforms on all NURBS controllers and Delete the History. Hide the Locators so they don't get in the way.

On one of the Controllers, create a new Attribute called "Aim_Ctrl" and key the aim constrain at 0 and 1. This will allow you to easily turn off the aim as needed. Sometimes, in environmental or locked off shots, it's easier to keep the camera without an aim.

Now that this simple rig is finished, you can see that the UNIVERSAL control will move both the aim position and the camera. Moving the GLOBAL or LOCAL will move the camera separately from the aim. You can constrain the GLOBAL aim controller to the subject, and move the LOCAL to recompose as needed.

This is just a start, the more controls you can add to make shooting fun and quick, the better!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)